He Thought “Titanic” Was a Grown-Up Toy

On my wife’s birthday, I bought her the Titanic DVD—peak 90s nostalgia, a little cheesy, totally our thing. Our three-year-old, Max, pointed at the case and asked, “Can I watch it after nursery school?”

“Not tonight, buddy,” I said. “It’s for grown-ups, like Mommy and Daddy.”

At pickup, his teacher was biting her lip to keep from laughing. “So… is this Titanic like… the ship?” she asked delicately.

“Yes,” I said, already flushing.

“Ah,” she nodded. “Because Max told everyone ‘Mommy and Daddy watch the Titanic alone at night because it’s for grown-ups only.’”

I had some explaining to do.

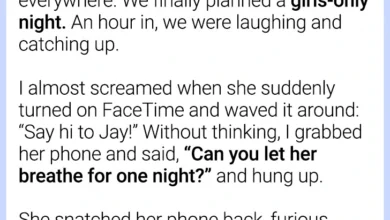

We told the story to friends for years—the Great Titanic Misunderstanding—and it never failed to break the ice. But the joke planted a seed. Max got obsessed with the ship. He drew oceans in crayon, lined shampoo bottles up as lifeboats, and asked the kind of questions that feel small until they don’t.

“Why didn’t the captain see the iceberg?” he asked over chicken nuggets.

“Sometimes people think they’re in control when they’re not,” I said. “They go too fast and don’t see danger coming.”

He dipped a fry, thinking. “I think that happened to you and Mommy.”

It landed like a quiet bell. Max had been a surprise. We’d sprinted—marriage, a mortgaged starter home, steady jobs we didn’t love. Co-captains on the same ship, rarely on the same deck.

That night my wife and I finally talked. Not a fight—just truths placed gently on the table. We started leaving work early on Fridays. She began painting again. I learned to close my laptop before bedtime. Nothing radical—just steering.

Max moved from ships to dinosaurs, then volcanoes, then space, but he never stopped being startlingly old-souled. At five he asked why I smiled when I was tired. At six he told my wife she should “write a book about her dreams.” At seven he said, “I think Grandpa visits in my sleep and we talk without mouths.”

We chalked it up to imagination… until Halifax. My wife had a conference, and a free afternoon wandered us into the Maritime Museum. Max stopped, transfixed by a weathered deck chair and a map of the North Atlantic.

“This is where it happened,” he whispered.

“Did you learn that in school?” my wife asked.

He shook his head. “I just know.”

That night we let him watch Titanic at last. He sat very still, hands knotted in his lap. When the credits rolled, he said, “They were too proud. That’s why it sank.” In the morning I found a note on the hotel notepad: Even the biggest ships need to be humble. Or they’ll sink.

He kept noticing what other people missed. He became the kid who’d sit on the porch with our gruff neighbor, Mr. Holland, and listen like it was the most important job in the world. At Mr. Holland’s funeral, Max raised his hand.

“I didn’t know him long,” he said, voice shaking, “but his smile changed when he talked about his wife. I think she heard that.”

By thirteen, our family looked different. We hadn’t outrun the weather so much as learned to read it. We switched to work that mattered more and paid a little less. We volunteered Saturday mornings. Dinner was sometimes soup and toast, but we ate it together. Max joined a youth mentorship group—not to be mentored, but to sit with kids who needed someone to listen.

One night after a meeting he was quiet in the passenger seat, watching the streetlights thread by.

“You okay, buddy?” I asked.

“A boy said his dad left,” he said. “I told him mine stayed. And I think staying is harder than leaving sometimes.”

I had to pull the car over.

“Thanks for staying, Dad.”

He grew up, as children insist on doing. Chose psychology—“People are like ships,” he said. “Some drift, some speed, some anchor too deep. But they all carry stories.” He wanted to hear them all.

On his graduation day, he handed us a flat, wrapped gift. Inside was our old Titanic DVD. Tucked in the case was a note in his precise, careful handwriting:

Thanks for helping me steer. Even when icebergs showed up. Love, your first mate—Max.

We cried, naturally. Then that night, after the party dishes were stacked in the sink and the house had exhaled, my wife and I pressed play. We didn’t fast-forward the sad parts. We didn’t talk over the score. We watched like we were reading an old map—tracing all the ways we’d once gone too fast, all the places we’d learned to slow down.

When the credits finally faded, my wife leaned into me and laughed softly. “Remember when the teachers thought we were watching a Titanic-themed… you know?”

“Oh, I remember,” I said. “Best accidental parenting lesson we ever got.”

Here’s what we learned from a three-year-old and a famously doomed ship:

Don’t speed through fog.

Name the iceberg before it names you.

Humility turns the wheel better than pride ever will.

And never underestimate the quiet kid in the back seat—he might be the only one reading the stars.

We started with a misunderstanding. We ended with a compass.

The Titanic didn’t save us. A child did—by asking the right question at the right time, and by reminding us that even the biggest ships need small, steady hands to steer them home.